Climate change, food insecurity and violent extremism in the Sahel: Reflections on the nexus under the new political dynamics

Climate change, food insecurity and violent extremism in the Sahel: Reflections on the nexus under the new political dynamics

Climate change, food insecurity and violent extremism in the Sahel: Reflections on the nexus under the new political dynamics

Samhita S. Ayaluri 1GCERF Performance and Impact Intern , Sai Aashirvad Konda 2GCERF Communications Associate, Emmanuel Nene Odjidja 3GCERF Performance and Impact and Assessments Specialist

With the recent coup in Burkina Faso, the political turmoil in the country has made headlines. However, political instability in the Sahel region of Africa has been an ongoing affair for more than a decade. The shortcomings of governance, civil wars, border insecurity, and violent extremism have plagued the region, recurring socio-economic issues for its people and its countries. Amidst the political imbalances is another pressing issue of climate change-induced food insecurity.

The Sahel region offers a notable illustration of the complex nexus between climate change and conflict. Of the ten countries in the Sahel, this article considers GCERF’s current partner countries: Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. For more than two decades, these three countries have been experiencing rising temperatures and are predicted to experience frequent and intense droughts in the coming years. This exacerbates the likelihood of conflict and insecurity in the region which is heavily dependent on natural resources for livelihood and food security. Climate change therefore acts as a ‘threat multiplier’ in the region and as an instrument for conflict. While the linkages between climate change and conflict remain complex, it is predominantly driven by two factors: resource scarcity and food insecurity.

One of the major types of conflict in Mali is over natural resources which includes increasing competition over its access, leading to desertification, degradation of fishing areas, and decrease in pastoral areas – the tragedy of the commons. This adversely affects the production, yield, and quality of life of rural populations. This, in addition to the existing effects of climate change (such as the increasing number of droughts, floods, and high temperatures) further weakens the production systems in a region that is currently experiencing a cumbersome political situation.

What does climate-induced food insecurity imply for violence within the region?

The Sahel’s food systems heavily depend upon precipitation and optimal temperatures. Agricultural productivity is negatively affected by climate change resulting in the loss of income and assets, decreasing purchasing power, driving up malnutrition and ultimately leading to food insecurity. The risk of food insecurity is high with an increasing number of reported conflicts and battles. In Mali, the conflict over high dependence on natural resources for livelihoods in addition to climate change affects the livelihoods of farmers and herders who constitute 80% of the Malian population. Their livelihoods are met with inter-group violent conflict.

This violence is largely rooted in competition over scarce natural resources. A pathway suggests that climate-related stresses result in reduced spaces of pasture for cattle and lower crop yield culminating in forced migration to newer territories already occupied by other groups, consequently resulting in violent conflicts. The infamous farmer-herder conflict between the Fulani pastoralist communities and the Bambara and Dogon farmer communities has been fatal, claiming 146 lives4Data on violence against civilians perpetrated by Pastoralists and Farmers (from the Fulani and the Dogon communities) recorded from ACLED. Data Export Tool – ACLED (acleddata.com). in just 2020 in Mali. Militant groups have exploited the fault lines of the inter-communal conflict to foster recruitment into their groups, making the current complex situation of violence unprecedented in the country.

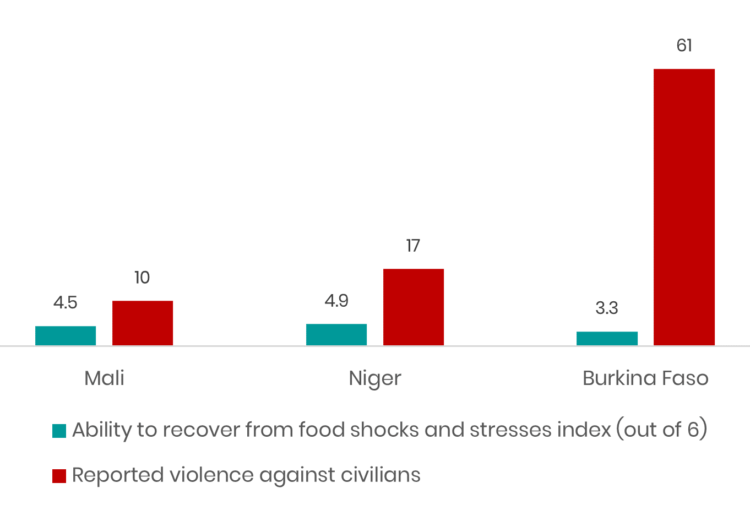

Using an indicator that measures perception of food security by analysing the present and future needs for food, it was observed that areas with low resilience to food shocks also had high numbers of reported cases of violence. In specific regions where data was collected between January and June of this year, communes in Burkina Faso with the least resilience (on a maximum scale of 6) had the highest number of reported cases of violence against civilians5Data on violence against civilians recorded from ACLED. Data Export Tool – ACLED (acleddata.com). Violence on civilian data is used in lieu of other forms of violence as it has direct consequences on human-related activities (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Comparison between the country’s ability to recover from food shocks and stresses and the reported level of violence against civilians (January to June 2022, ACLED)

The intersection of food insecurity and existing communal tensions along with other contributing factors such as unemployment, gender inequalities and lack of opportunities provide a breeding ground for extremist violence, adversely affecting the livelihoods of the people.

How is GCERF approaching this gloomy nexus in the region?

Addressing the link between the two phenomena is complex and intertwined in an existing context of conflict and vulnerability. GCERF, through its focus on youth, women, religious and traditional leaders, students, and local authorities, approaches this via three interconnected interventions:

- Regeneration of previously climate-distressed land through apt management and practices (200 hectares planned): this helps with improving the soil quality and helps farmers and herders reclaim the land in a peaceful manner;

- Development of water pumps for livestock; and

- Diversification of livelihoods and formation of cooperatives.

GCERF programming in the region also creates frameworks for consultation and promotion of peaceful cohabitation, collects demographic information on the location and status of natural resources, and livestock markets, monitors conflict risks, and disseminates information to strengthen the capacities and responsibilities of communities in crisis prevention and management. Through its activities, the GCERF-funded programmes aim to strengthen intergenerational social cohesion in the region, while also aiming to subdue the environmental implications and reduce the risk of climate-change effects on the inter-communal violence and livelihoods of the affected people.

Climate change as an underlying factor for the political instability in the Sahel should not be understated. There is a need for a new whole-of-society approach with climate change at its centre to mitigate the consequences of conflict in the region.

Image: A herder with his livestock in Burkina Faso. BOULENGER Xavier / Shutterstock.com